In a constitutional question being heard in Provincial court in Amherst, Nova Scotia, a Federal Crown brief claims “The status of the 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty in 2025 is uncertain – either to whom it applies or whether it applies.” Breaking from Supreme Court precedent, the court also barred Indigenous leaders from testifying about their interpretation of the treaty unless they were qualified as “expert witnesses.”

AMHERST, NS – On Monday, August 25th, 2025 Crown prosecutor Len MacKay filed a legal brief seeking the summary dismissal of the treaty portion of a constitutional challenge filed by Micmac Rights Association member Connor Paul. The following day was spent hearing Mr. Paul’s challenge, with Judge Rosalind Michie presiding.

Mr. Paul, a status Indian whose biological father is from Sipekne’katik, holds that section 802.1 of Canada’s Criminal Code – which prevents him from being represented by Chief Riley because he is facing more than six months of jail time – is a violation of his constitutionally protected Aboriginal and treaty rights to be represented by an Indigenous knowledge holder in court.

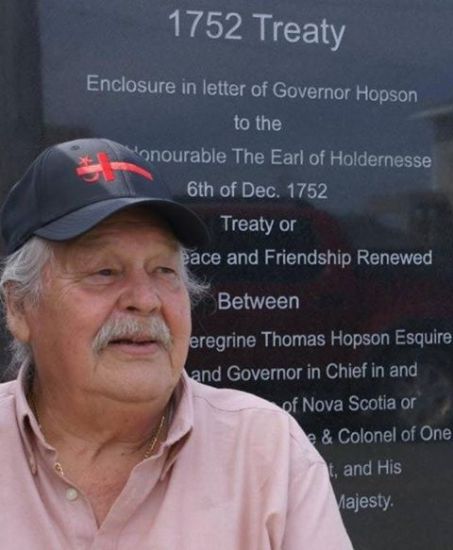

Former National Chief Delbert Riley was responsible for entrenching Aboriginal and treaty rights in the Canadian constitution in the early 1990s. Though now in his 80s, Chief Riley remains very active. He and his assistant Tom Keefer have successfully defended a number of MRA members before the courts by acting as their agents and providing a ‘traditional treaty defence’ grounded in inherent Indigenous rights and sections 25 and 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act.

The constitutional brief on the representation of Mi’kmaw people by their elders filed by Chief Riley quotes the Treaty of 1752 as providing a treaty right for Mi’kmaw people to be represented as they choose to be. Article 8 of the Treaty reads:

“That all Disputes whatsoever that may happen to arise between the Indians now at Peace, and others His Majesty’s Subjects in this Province shall be tryed in His Majesty’s Courts of Civil Judicature, where the Indians shall have the same benefit, Advantages and Priviledges, as any others of His Majesty’s Subjects.”

Chief Riley argues that this treaty right amounts to a guarantee from the Crown for a “racism free” trial in which Mi’kmaw concerns can be fully aired and addressed on a basis of equality and fairness. Equal “benefit” and “privileges” in court include the right for Mi’kmaw people to be able to choose their own representatives to articulate their case effectively. According to Chief Riley, it is wrong and runs counter to the Treaty to require representation from Canadian lawyers organized by provincial law societies to speak about Indigenous issues. As the legal brief notes, “Just as a British subject could choose someone knowledgeable to represent them, so too the Mi’kmaw must be permitted to be represented by their own trusted advocates, consistent with their customs (e.g. a respected elder or leader).”

In his affidavit, Connor Paul stated that “I think that having the Indigenous leader who put sections 25 and 35 in Canada’s Constitution explain to the court what the Indigenous intention was in negotiating these protections for Aboriginal and treaty rights will be key to winning my case. I don’t believe that lawyers that swear an oath to the Crown and who are fundamentally a part of the Canadian legal system are truly able to understand the Indigenous experience or have the same motivation to fight for our rights and interests in the way that Indigenous elders such as Chief Riley will.”

Further evidence in the form of affidavits was also submitted by Connor Paul. These included several affidavits outlining Connor Paul’s family history and connection to Sipekne’katik, as well as affidavits in support of his Aboriginal and treaty rights from former National Chief Del Riley, Micmac Rights Association founder and elected Millbrook First Nation Councillor Chris Googoo, and renowned Mi’kmaw knowledgeholder Dr. Albert Marshall Sr.

Crown Brief claims Supreme Court Decision no longer applies

In the August 25th brief filed by Crown Prosecutor Len MacKay, the Crown stated that because the defence does not “propose to call expert evidence to establish the nature of the treaty, the historical context of the treaty, the application of the treaty, or the intentions of the parties to the treaty” there is an “absence of an evidentiary foundation.” Because of this lack of foundation, and the “mere assertion of its [the treaty’s] applicability” [emphasis added] MacKay argued that the Treaty rights claim in the matter should be “summarily dismissed” (ie. the Judge should not even consider the treaty arguments being made by Mr. Paul.)

Len MacKay is a senior prosecutor who once led the Association of Justice Counsel (the representative organization for approximately 3,500 lawyers employed by the federal government). He is the main federal Crown handling the prosecution of the s. 35 constitutional claims being advanced by MRA members, and has advised police officials such as RCMP Supt. Jason Popik who carried out the 13 raids of so-called “Project Highfield” in February of 2025.

In his brief, MacKay wrote, “The status of the 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty in 2025 is uncertain – either to whom it applies or whether it applies.” In R. v. Simon (1985), the Supreme Court of Canada held that the Crown had not led sufficient evidence at trial for the Court to reach a finding that the treaty had been terminated for breach of its core provisions. Compelling evidence was led in R. v. Marshall (“Marshall 1”) causing the defendants to abandon their reliance on that treaty at the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal and Supreme Court of Canada. At least one Court has held that the 1752 treaty had been terminated by subsequent hostilities.6 Following Marshall 1, the 1760-61 treaties are clearly in effect today.”

This position is remarkable because the Supreme Court of Canada already ruled in Simon v. the Queen over 40 years ago that the Treaty of 1752 was an “enforceable obligation” on both parties and “is of as much force and effect today as it was at the time it was concluded.” The court also ruled on the matter of whether the Treaty was broken after it was signed and decided that it wasn’t. The pattern of summary dismissal of Aboriginal and treaty rights seems to be a common tactic utilized by the Federal Crown. The tactic was unsuccessfully attempted by the Crown in Cody Caplin’s constitutional trial which Chief Riley won after the Crown dropped all charges, but was successfully utilized by Provincial Judge Rhonda van der Hoek to avoid taking on the Mi’kmaq constitutional arguments.

In his brief, MacKay noted that:

“The Crown’s position is that, without a proper evidentiary foundation [concerning the applicability of the Treaty of 1752], neither the Crown nor the Court can properly assess the merits of the application. Where, as here, the defendants cannot point to any anticipated evidence that is capable of establishing the factual foundation necessary to support their application, the application should be rejected as manifestly frivolous until such time as the defendants propose evidence capable of supporting their application.” MacKay added, “In order to know whether the Treaty of 1752 applies, the Court needs the evidence of experts.”

What the Supreme Court of Canada said about the Treaty of 1752

It is difficult to explain what a massive slap in the face to Mi’kmaw rights holders the Crown’s brief is. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled 40 years ago in its groundbreaking Simon v. the Queen decision that the treaty is “an enforceable obligation between the Indians and the Crown.” The court added that:

“The Treaty of 1752 continues to be in force and effect. The principles of international treaty law relating to treaty termination were not determinative because an Indian treaty is unique and sui generis. Furthermore, nothing in the British conduct subsequent to the conclusion of the Treaty or in the hostilities of 1753 indicated that the Crown considered the terms of the Treaty terminated.”

Concerning the issue of the applicability of the treaty, which MacKay suggested remained uncertain, the Supreme Court gave a clear and unambiguous answer:

“Appellant is an Indian covered by the Treaty. He was a registered Micmac Indian living in the same area as the original Micmac Indian tribe which was a party to the Treaty. This was sufficient evidence to prove appellant’s connection to that tribe. In light of the Micmac tradition of not committing things to writing, to require more, such as proving direct descendancy, would be impossible and render nugatory any right to hunt that a present day Micmac would otherwise have.”

Connor Paul is a registered Micmac Indian directly descended from the same original “Tribe of Mick Mack Indians Inhabiting the Eastern Coast of the said Province” who signed the treaty. This group of Mi’kmaq people fought the British under Governor Cornwallis for control of mainland Nova Scotia beginning in 1749 when Cornwallis landed 5000 settlers to take control of what is now known as Halifax. After two years of warfare, Corwallis gave up and was replaced. As the Supreme Court of Canada noted:

“The Treaty was entered into for the benefit of both the British Crown and the Micmac people, to maintain peace and order as well as to recognize and confirm the existing hunting and fishing rights of the Micmac. In my opinion, both the Governor and the Micmac entered into the Treaty with the intention of creating mutually binding obligations which would be solemnly respected. It also provided a mechanism for dispute resolution. …. I would hold that the Treaty of 1752 was validly created by competent parties.”

Of direct relevance to the issue of representation under s. 802.1, the Simon ruling stated that the Treaty was a “positive source of protection against infringements on hunting rights” upon which the appellant could rely and not “merely a general acknowledgement of pre‑existing non‑treaty aboriginal rights.” A similar such argument can be made in regards to Article 8 of the Treaty and Mi’kmaw interactions with the Crown’s courts of civil judicature. According to the Supreme Court:

“Such an interpretation accords with the generally accepted view that Indian treaties should be given a fair, large and liberal construction in favour of the Indians. This principle of interpretation was most recently affirmed by this Court in Nowegijick v. The Queen, 1983 CanLII 18 (SCC), [1983] 1 S.C.R. 29. I had occasion to say the following at p. 36:

The Supreme Court of Canada is Canada’s highest level court, its decisions are binding upon lower courts and cannot be overturned by them, or by the whims of a Crown prosecutor. According to Chief Riley, “The Crown is correct that we have not attempted to provide an “evidentiary foundation” to prove the applicability of the Treaty. We don’t have to. The Supreme Court of Canada has already done so and ruled on these matters.”

How the Supreme Court of Canada says treaties should be interpreted

The matter at issue in the 802.1 NCQ is the interpretation of the terms of the 1752 treaty. As the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in R. v. Badger, [1996] 1 S.C.R. 771 a leading case on the scope of Aboriginal and treaty rights:

“Certain principles apply in interpreting a treaty. First, a treaty represents an exchange of solemn promises between the Crown and the various Indian nations. Second, the honour of the Crown is always at stake; the Crown must be assumed to intend to fulfil its promises. No appearance of ‘sharp dealing’ will be sanctioned. Third, any ambiguities or doubtful expressions must be resolved in favour of the Indians and any limitations restricting the rights of Indians under treaties must be narrowly construed. Finally, the onus of establishing strict proof of extinguishment of a treaty or aboriginal right lies upon the Crown.”

The Crown’s standard pro-forma legal brief that Len MacKay has used in a number of cases to inform the courts of the status of Aboriginal and treaty rights is over 20 years out of date. It contains not a single legal case after the 2006 Supreme Court Ruling R. v. Sappier; R. v. Gray and has no mention of UNDRIPA or various other Supreme Court rulings on Aboriginal and treaty rights in the last two decades. It is unclear what the reason for this lack of professionalism and rigour is.

According to Chief Riley, “It could be incompetence, but given their refusal to acknowledge the Treaty of 1752, it might also just be racism.” The Chief noted that this racism might be colouring the refusal to accept the changing face of Aboriginal and treaty law in Canada – which has seen a steady stream of s. 35 decisions in favour of Aboriginal and treaty rights holders in recent years.

As the Supreme Court of Canada decided in Ontario (Attorney General) v. Restoule, 2024 SCC 27 in summarizing its understanding of treaty rights:

“Treaties are sui generis agreements intended to advance reconciliation. The Crown’s assertion of sovereignty gave rise to a distinctive legal relationship between the Crown and Indigenous peoples. That distinctive legal relationship is reflected in treaties, which represent an exchange of solemn promises and are governed by special rules of interpretation. In order to promote reconciliation, treaty rights must be interpreted and implemented in accordance with the honour of the Crown — the principle that servants of the Crown must conduct themselves with honour when acting on behalf of the sovereign.

Although all treaty rights must be interpreted in accordance with the honour of the Crown, there are important differences between historic (pre-1921) and modern (post-1973) treaties. The words in an historic treaty must not be interpreted in their strict technical sense nor subjected to rigid modern rules of interpretation. They should be liberally construed and ambiguities or doubtful expressions should be resolved in favour of the Indigenous signatories.

The goal of treaty interpretation is to choose from among the various possible interpretations of common intention the one which best reconciles the interests of both parties at the time the treaty was signed. In searching for the common intention of the parties, the integrity and honour of the Crown is presumed. The court must be sensitive to the unique cultural and linguistic differences between the parties, and the words of the treaty must be given the sense which they would naturally have held for the parties at the time. While construing the language generously, the court cannot alter the terms of the treaty by exceeding what is possible or realistic.

Treaty rights must not be interpreted in a static or rigid way; they are not frozen at the date of signature. Because a court must consider both the words of a treaty and the historical and cultural context, it is useful to approach treaty interpretation in two steps: at the first step, the court focuses on the words of the treaty clause at issue and identifies the range of possible interpretations, and at the second step, the court considers those interpretations against the treaty’s historical and cultural backdrop.

The standard of review for the interpretation of historic treaties is correctness.

The constitutional nature of treaties as nation-to-nation agreements that engage the honour of the Crown and the process of reconciliation itself demands that appellate courts be given wide latitude to correct errors in their interpretation when necessary. The perpetual, multi-generational nature of treaty rights calls for the consistency of interpretation that is the goal of correctness review. A court’s interpretation of treaty rights will be binding in perpetuity and has a significant precedential character.

In addition, historic Crown-Indigenous treaties are binding not only on their direct signatories; they are binding upon all Canadians who, because of the Crown’s assertion of sovereignty, are also effectively implicated. A court’s interpretation of an historic treaty thus has extensive normative reach, which further supports correctness review.”

The next court date in this matter will be held on Wednesday, Sept 24th at the Provincial Court in Amherst at 9:30am. The MRA encourages all of its members and supporters to attend.